American Chips Are Still Powering Russian Missiles—And the Trail Leads Back to Us

KYIV — The missile that tore through the apartment building arrived without warning on a cold February morning. After the dust settled and survivors were pulled from the rubble, Ukrainian investigators began their grim work: cataloging the weapon’s remains.

What they found has become routine—and damning.

Tucked inside the wreckage were American-made microchips. Not surplus from the Cold War. Not knockoffs from black markets. These were genuine components, some manufactured just five months earlier in September 2025.

“Every time we dig through the debris, we find the same thing,” says a Ukrainian forensic investigator who requested anonymity. “The West’s technology. The West’s engineering. Killing Ukrainian civilians.”

The Uncomfortable Truth

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy recently called it an “embarrassment for the West.” He’s not exaggerating.

After 19 rounds of sanctions by the U.S. and European Union, Russia’s weapons are more sophisticated than ever. A single October attack involved 500 drones and 50 missiles. Investigators recovered over 100,000 foreign-made components from the wreckage.

The question everyone’s asking: How is this still happening?

Follow the Chips

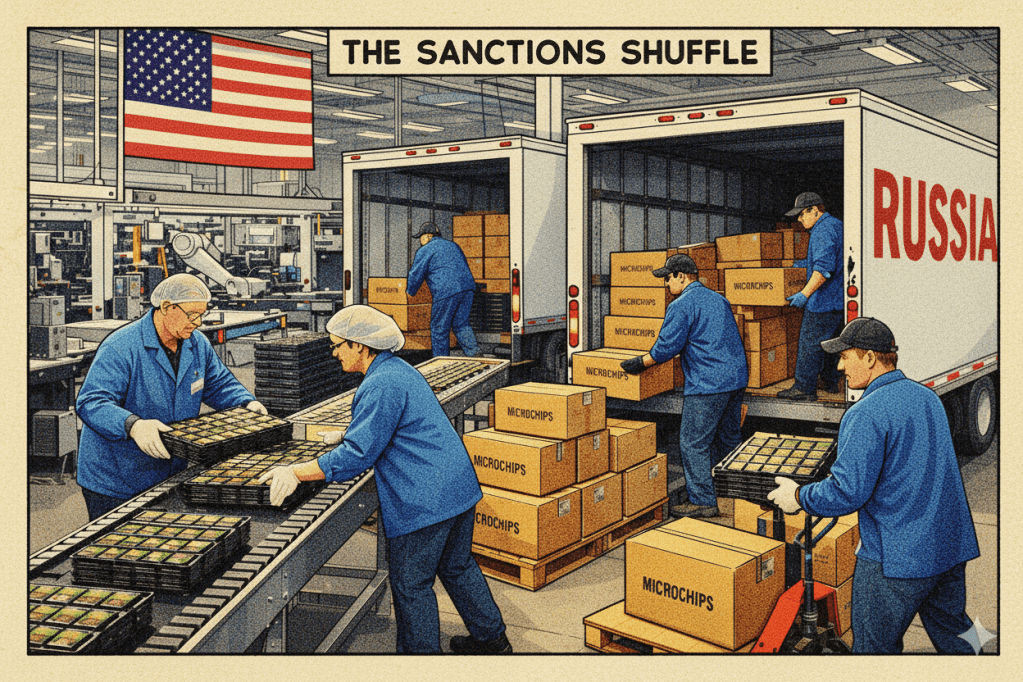

The answer lies in a global shell game that makes sanctions look like theater.

Russia doesn’t buy directly from Texas or Germany anymore. It doesn’t have to. The path looks something like this:

- American manufacturer sells chips to a distributor in Dubai

- Dubai distributor sells to a shell company in Hong Kong

- Shell company routes them through Malaysia

- Russian factory assembles them into cruise missiles

By the time the chip reaches Moscow, the paper trail has gone cold—and everyone along the chain can claim plausible deniability.

What’s Inside Russia’s Arsenal

Ukrainian investigators have essentially become tech archaeologists. Here’s what they’re finding:

The Newest Drones (Geran-5)

- Clock oscillators from Texas-based CTS Corporation

- Power modules from Germany’s Infineon Technologies

Cruise Missiles (Kh-101)

- American-made converters and sensors

- Used specifically to target Ukrainian power plants

The Pipeline

Roughly 2.2 million electronic components reached Russia in 2025 alone, primarily through intermediaries in China, UAE, and Malaysia.

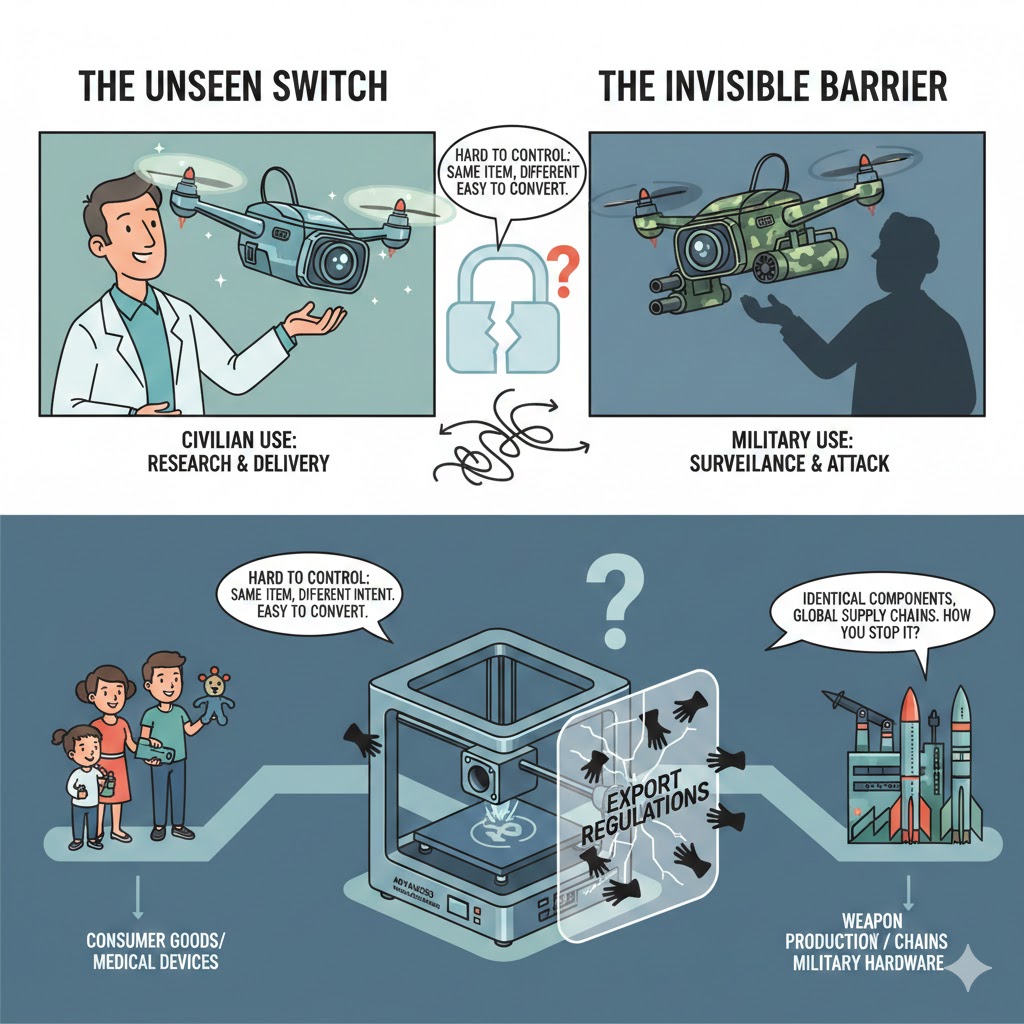

The “Dual-Use” Problem

Here’s where it gets complicated. The chips found in Russian missiles aren’t military-grade supercomputers. They’re the same components you’d find in:

- Car dashboards

- Industrial washing machines

- Medical equipment

- Consumer electronics

Banning them entirely would cripple global supply chains and devastate Western manufacturers. Russia knows this. It’s counting on it.

“They’re hiding weapons in plain sight,” explains a NATO analyst. “The same chip that helps your dishwasher run also guides a missile.”

Who’s Responsible?

In December 2025, Ukrainian civilians filed lawsuits against several major U.S. chipmakers in Texas courts. Their argument: these companies have the technology to track where their products end up. They just choose not to look.

Why? The sales remain profitable. And as long as the transactions happen through intermediaries, manufacturers can maintain they didn’t “knowingly” supply Russia.

One industry insider, speaking on background, put it bluntly: “Everyone knows what’s happening. But proving intent is nearly impossible when there are five shell companies between you and Moscow.”

The Enforcement Gap

Western governments insist they’re tightening controls. In January 2026, the U.S. Treasury issued new restrictions aimed at closing loopholes. Congress introduced the DROP Act to target the shadow shipping networks that move these components.

But here’s the math that doesn’t work: It takes investigators years to untangle these networks. Russia can procure components and launch missiles in months.

“We’re playing checkers while they’re playing speed chess,” says a European sanctions official.

What Happens Next?

By mid-2026, the G7 is expected to debate a radical new approach: requiring manufacturers to verify the actual end-user of sensitive electronics, not just the first buyer.

Think of it as “know your customer’s customer’s customer.”

The resistance is already building. Such tracking would create massive administrative burdens, slow down supply chains, and potentially cost Western companies billions in lost sales.

Which raises the uncomfortable question hanging over all of this: Is the West willing to accept economic pain to stop supplying the weapons killing Ukrainian civilians?

So far, the answer—written in the wreckage of apartment buildings across Ukraine—appears to be no.

Leave a comment