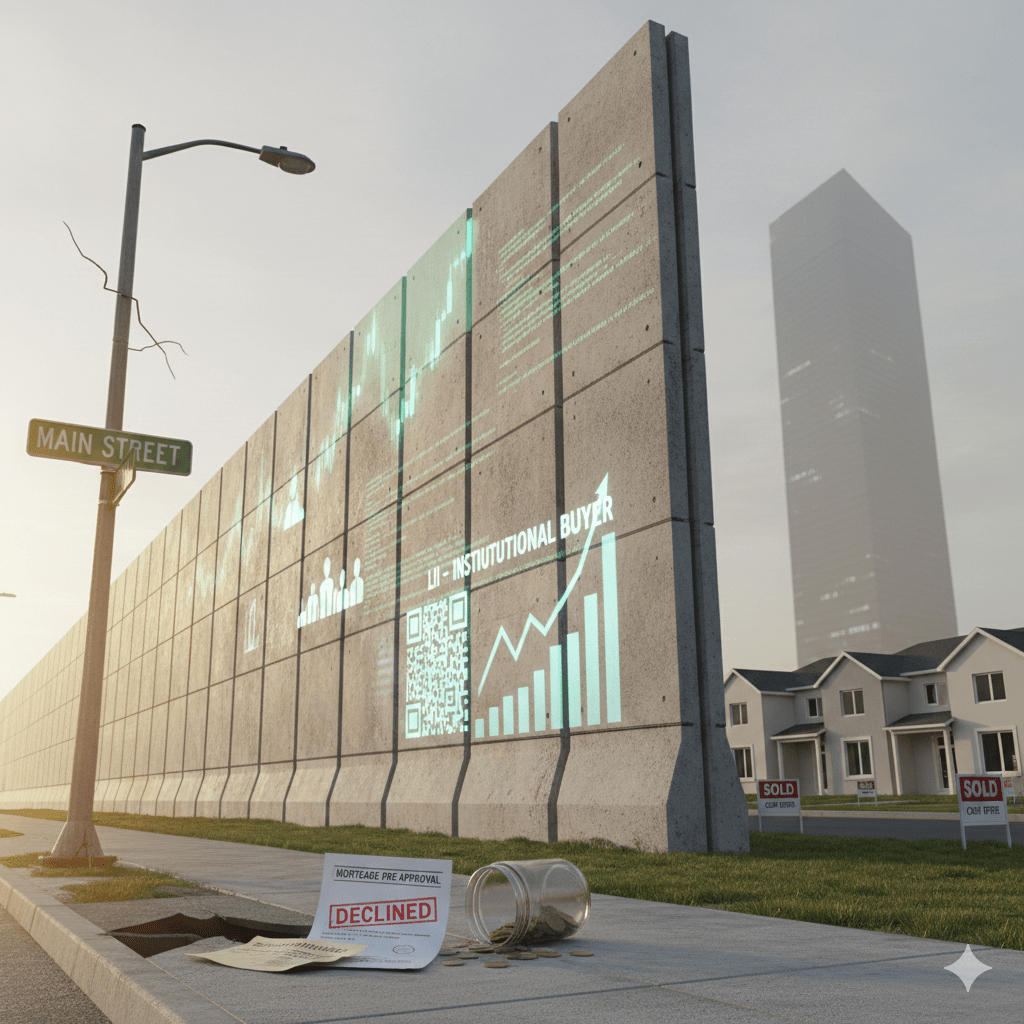

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — The American housing market is no longer a marketplace. It is a battleground — one where families armed with pre‑approval letters are being steamrolled by corporate buying algorithms, tightening credit systems, and a political class that keeps promising solutions while quietly protecting the very forces driving the crisis.

Mortgage rates may have stabilized in the low‑6% range, but the real story of 2026 is not interest rates. It is the rise of the institutional buyer, the silent tightening of credit, and a federal government scrambling to look like it’s fighting for “Main Street” while the structural machinery of the crisis remains largely untouched.

This is not a bubble. It is a controlled squeeze — and millions of Americans are stuck in the vise.

The Corporate Landlord Machine

In cities from Phoenix to Charlotte, families are discovering that they aren’t losing bidding wars — they’re losing to software. Large Institutional Investors (LIIs) now deploy automated buying bots capable of placing offers within minutes of a listing going live. These aren’t investors “competing” with families; they are industrial‑scale acquisition engines.

The result is a market where homes are no longer purchased — they are harvested.

Politicians have finally begun naming the problem. California Governor Gavin Newsom has proposed restrictions on corporate ownership of single‑family homes. Federal officials have echoed the concern. But the scale of institutional ownership is already reshaping entire zip codes, and the policy response remains fragmented and reactive.

The “Main Street” Executive Order — Symbol or Solution

On January 20, 2026, President Donald Trump signed the executive order “Stopping Wall Street from Competing with Main Street Homebuyers.” The directive instructs federal agencies to stop approving or insuring the sale of single‑family homes to corporate entities when those homes could otherwise go to families. It is the most aggressive federal intervention in the private real‑estate market in decades — and yet, its impact remains uncertain.

“We are ending the era of the corporate neighborhood,” a White House economic advisor declared. But the order does not unwind existing corporate holdings, nor does it address the algorithmic buying systems that dominate the market. It gives families a “first‑look” window on foreclosures, but not on the open market where most institutional acquisitions occur.

In other words: it’s a political shot across the bow, not a structural fix.

Renters Are Paying for the Crisis Twice

While the political fight centers on homeownership, renters are absorbing the shock in real time. After a brief post‑pandemic lull, rents surged again through 2025 and into 2026. The return to urban centers, combined with years of underbuilding, has created a supply shortage that corporate landlords have been quick to monetize.

Rent inflation continues to outpace wage growth, pushing families deeper into debt and further from the possibility of buying a home. The affordability gap is widening into a chasm — and the downstream effects are becoming impossible to ignore: delayed family formation, rising homelessness, and increased reliance on high‑interest credit.

Credit Tightening: The Barrier No One Voted For

Even as the federal government targets corporate buyers, the average borrower faces a different — and far quieter — obstacle: a credit market that has slammed shut.

Despite the Federal Reserve holding interest rates steady at 3.5% to 3.75%, commercial banks have raised lending standards across the board. Automated underwriting systems now reject applicants with even modest debt loads, creating what analysts call a “Credit Freeze.”

The Debt‑to‑Income Trap

Rent inflation has pushed many young professionals into higher debt‑to‑income ratios, triggering automatic denials from lending algorithms.

The ARM Gamble

Roughly 10% of new mortgage volume is now in Adjustable‑Rate Mortgages — the highest share since 2023 — as buyers bet on future rate cuts.

The Down Payment Divide

With institutional buyers offering cash, traditional buyers must bring larger down payments to compete, widening the gap between those with generational wealth and those without.

This is not a free market. It is a filtering system — one that increasingly rewards asset holders and punishes wage earners.

The Landlord Lobby Strikes Back

Institutional investors insist they are not the villains. They argue that corporate landlords provide professional management and essential rental supply in a market where many cannot afford to buy.

“If you ban large operators from building or buying, you aren’t creating homeowners; you’re just creating a shortage of quality rentals,” said Michael Rehaut, an analyst at J.P. Morgan.

But this defense ignores the obvious: institutional investors are not filling a gap — they are exploiting one. And the OBBBA’s regulatory changes, combined with new tariffs on steel and copper, have already slowed new construction to late‑2010 levels. Restricting institutional capital may tighten supply further, but allowing unfettered corporate acquisition has already distorted the market beyond recognition.

The question is not whether institutional investors provide value. It is whether they should be allowed to dominate a market that was never designed for them.

A Market Too Expensive to Buy, Too Scarce to Crash

All eyes are now on the Federal Reserve’s March 18 meeting. A surprise quarter‑point cut could provide a psychological boost to the spring buying season. But the underlying math remains bleak.

For the millions of Americans searching “2026 housing crash,” the reality is more likely a stall than a collapse. National home prices are forecast to remain flat — a tense equilibrium where homes are too expensive for buyers but too scarce to trigger a downturn.

This “frozen market” is the worst of both worlds:

- no affordability relief,

- no inventory surge,

- no price correction,

- and no political consensus on what to do next.

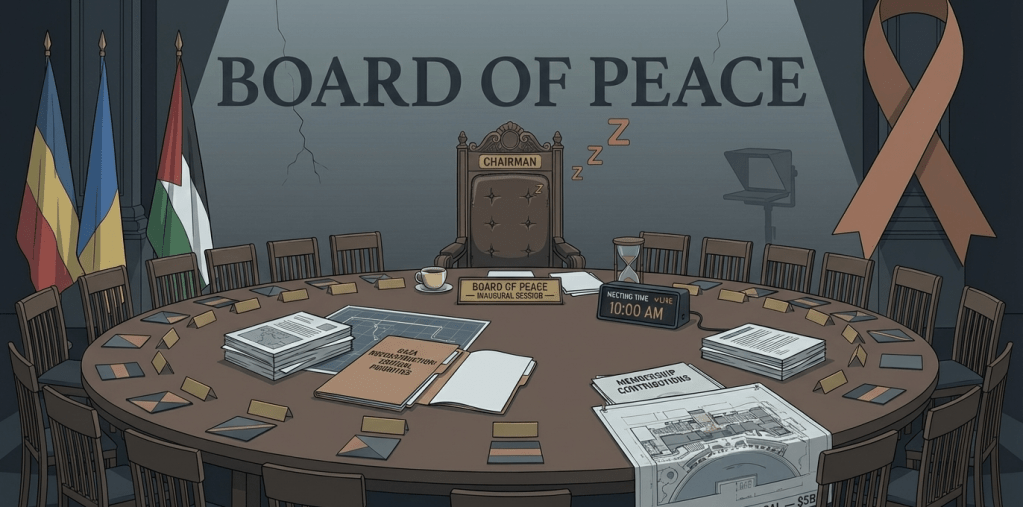

The Fight Over Who Owns America

The housing and credit crunch is not a natural disaster. It is the predictable outcome of decades of underbuilding, financialization, and policy drift. Corporate landlords are part of the story, but so are restrictive zoning laws, stagnant wages, and a financial system that increasingly rewards capital over labor.

What makes 2026 different is the public’s growing recognition that the system is not malfunctioning — it is functioning exactly as designed.

The fight over who owns America’s homes — and who gets to live in them — is no longer a policy debate. It is a struggle over economic power, political identity, and the future of the middle class.

And for now, the people losing that fight are the ones who still believe the housing market was built for them.

Leave a comment